BDCs: Out of the Box

by JohnPublicly traded Business Development Companies (BDCs) are an interesting type of investment because they don’t fit neatly into a single asset class. Are they stocks? Fixed income? Alternatives? You could make a solid case for any of those categories. I think that’s part of the reason why BDCs are often overlooked.

Most stock and bond managers leave BDCs out of their investment universe. And since BDCs trade publicly, I doubt many investors or allocators think of them as alternatives either. It’s still not clear who the “natural” buyer of a BDC really is. When you look at the ownership data of BDCs, it tends to be very different from other stocks. Because of this, I think the space is full of inefficiencies—and opportunities.

Private Credit for Everyone

You can get a full overview of the BDC structure on Investopedia, but to over simplify, many BDCs are just private credit or middle-market lending funds that trade like stocks. Some BDCs do make equity investments, but here I’m highlighting the ones that are debt-focused.

It’s ironic that asset managers have been rushing to launch “accessible” private credit funds because BDCs have already been offering this for decades—no investment minimums, no investor status requirements, no subscription docs, and no lockups.

While there are some differences between public BDCs, non-traded BDCs (like interval or tender offer funds), and drawdown private credit funds, the biggest difference is volatility. But the underlying loans are often the same across all formats. Since public BDCs are priced daily, they can trade well above or below their net asset value (NAV), creating even more opportunities.

Show Me the Money

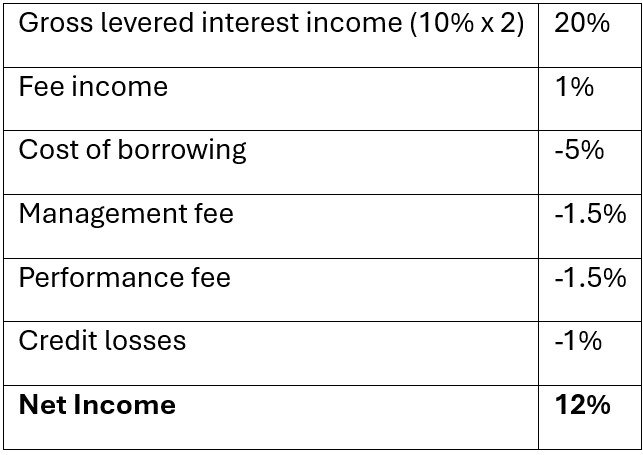

One way to evaluate a BDC’s risk and reward is to break down its income and expenses—especially because most BDCs use lots of leverage. Here’s an example of a BDC that makes loans paying an average of 10%, using one turn of leverage on the portfolio:

As you can see, the gross return gets chipped away quite a bit by expenses. Now, take the same BDC structure but with lower costs:

In this example, you get 2% more income without taking on any more risk. That’s why paying attention to fees and leverage really matters. Credit quality obviously plays a major role so you can never ignore that. But costs make a good starting point because evaluating underwriting is subjective. On the other hand, expenses are public and measurable—and they immediately and directly impact your return.

A site like CEFdata.com is a great resource for comparing BDCs based on leverage, fees, and how much they’re trading above or below NAV. [Note from Hunter: I have also found CEFConnect.com from Nuveen to be a valuable resource.]

Discounts & Premiums

Since BDCs are publicly traded, their price is set by the market—not an appraisal or committee. That means they can trade at big discounts to NAV, especially when credit markets are distressed. These discounts can often more than make up for high fees or mild credit losses.

On the flip side, premiums tend to be smaller. When you do see large premiums, it’s usually in BDCs with more equity exposure—like Hercules Capital ($HTGC). But even debt-focused BDCs can trade at 10–15% premiums.

Some might argue that these discounts and premiums accurately reflect risks and market sentiment. But historically, credit losses in BDCs have been relatively modest compared to other high-yield debt. That suggests inefficiencies—likely due to their unique structure—rather than just risk.

Key Takeaways

BDCs aren’t for everyone. They come with volatility and tax inefficiencies that may be deal breakers for some. Also, buying the whole BDC market blindly probably isn’t the best strategy, although there is an index fund available.

That said, BDCs can play a valuable role in many portfolios under the right conditions. If you can buy a BDCs with reasonable expenses and solid-performing loans at a significant discount, you can often build in a solid cushion against potential credit losses and still earn a strong return.

BDCs may work well as growth vehicles in tax-exempt accounts like IRAs or foundations. They can also be a substitute for illiquid private credit or high-yield bonds as part of a barbell fixed income strategy. My favorite use case is buying them opportunistically when credit markets are distressed. During COVID, for example, BDCs traded at discounts of 40–50%.

There’s more to explore here, and I may dive deeper in a future post. But for now, the bottom line is: BDCs deserve a closer look—especially when they’re trading at large discounts to NAV.